Pure Land Reflections on the Poems:

Pure Land Reflections on the Poems:

It is relatively difficult to directly attain the ideal ‘Zen’ state of total non-attachment to any mental or physical phenomena (which would really be equal to being liberated already – as in the Sixth Patriarch’s case, as exemplified by his poem, which is the second below), as the mind will usually habitually attach to some thing at any one moment. When the mind is this undisciplined and thus fickle, it also jumps from one subject to another with little rest.

In Pure Land practice, the above problems are clearly recognised – which is why the name of Amituofo is used as a subject of meditation (chanting) – to rein in the wandering mind. This is the aspect of practice that is similar in effect to Samatha meditation (for calming and focusing the mind). (For comparisons of Pureland practice with Samatha and Vipassana meditation, please see https://purelanders.com/2009/09/14/pure-land-practice-with-samatha-vipassana-meditation)

The use of Amituofo’s name is an especially skilful subject. Beyond helping to calm and focus the mind, which mindfulness of breathing does too, mindfulness of Buddha helps us tune to our Buddha-nature too, while connecting to the blessings of Amituofo (and all other Buddhas), while training to be born in his Pure Land – where enlightenment is guaranteed. This is the excellent extra edge. Let us now look at the two famous poems in the Platform Sutra…

身是菩提树 (Shen Shi Pu Ti Shu)

心如明镜台 (Xin Ru Ming Jing Tai)

时时勤拂试 (Shi Shi Qin Fu Shi)

莫使惹尘埃 (Mo Shi Re Chen Ai)

The body is the Bodhi tree

The mind is like a bright mirror stand

Moment to moment, diligently wipe

To let no dust alight

As long as we have form and/or are attached to form to some extent, we have to rely on and use form skilfully. Even the name of Amituofo is a subtle ‘form’. Even Pure Land itself has the finest and most skilful of forms, which teach the Dharma. The name of Amituofo represents the Bodhi (awakening) too, as it is the name of an awakened one. As we have yet to realise true emptiness (sunyata) of the mind, we have to diligently ‘wipe’ the mirror of our mind to prevent dust (of defilements) from alighting on it. When we are continuously mindful of Amituofo well, this instantly wipes off whatever dust that has settled on the mind in the moment, and prevents new dust from alighting. With improved practice, less and less dust will alight – even when we are not being mindful of Amituofo.

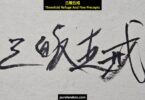

菩提本无树 (Pu Ti Ben Wu Shu)

明镜亦非台 (Ming Jing Yi Fei Tai)

本来无一物 (Ben Lai Wu Yi Wu)

何处惹尘埃 (He Chu Re Chen Ai)

Bodhi originally has no tree

The bright mirror also has no stand

Originally there is not a thing

Where can dust alight?

This poem describes the liberated mind – which Pure Land practitioners hope to attain too. However, even if this is not realised in this lifetime, it is alright for them – as long as birth in Pure Land is ensured, where liberation will surely be attained. In short, the poem states liberation as being non-attachment to body (matter) and mind, Bodhi (enlightenment) and dust (defilements). This is the realisation of emptiness of all worldly and thus conditioned phenomena. Even Bodhi that is attained is not attached to.

Pure Land practitioners can realise the above when the mind that abides in the name of Amituofo (and nothing else) lets go of the subtlest attachment to the name itself. This is the state of ‘chanting without chanting’ (念而无念: Nian Er Wu Nian). This is when one is truly one with Amituofo, yet without attachment to Amituofo or anything else. When one is perfectly mindful of a Buddha, one becomes a perfect Buddha (as only a Buddha can be perfectly mindful of another Buddha). (Note that even Bodhisattvas in the final stage of training need to practise mindfulness of Buddha – as ‘Buddha’ represents their ideal.) As such, it is not required to be perfectly mindful of Buddha to be reborn in a Buddha’s Pure Land. One just needs to be sufficiently mindful, with sufficient single-mindedness, for sufficient time – before passing away.